Bipolar can be subtle and hard to detect, which is ironic considering how outlandish someone could become during a period of mania. It’s then difficult to recognise, adjust and treat bipolar. Consequently, over 60% of people who screened bipolar positive from an NHS Digital study were not getting the correct treatment. Joseph Reaidi looks into the lives of two people with type-two bipolar and how they recognised and adapted to bipolar.

RECOGNISING BIPOLAR

Like most people with bipolar, Ames Elliot was misdiagnosed with major depression, which wasn’t corrected until 35-years-old.

“I would see a therapist when I was depressed, so when I started feeling better, I’d think I’m fine again,” recalls Ames. It didn’t occur to her that this better feeling could be in fact hypomania.

“I was functioning, I was successful,” says Ames “I thought I just had a restless spirit.” Restlessness seemed normal to her, even when her husband thought otherwise. “I would go through a cycle where I’d want to change everything. I’d obsessively focus on how I’d leave certain circumstances and start fresh,” she reveals.

Ames thought she was adventurous by constantly changing US states in her early adult life. In reality, she never had enough time to settle and build a substantial career.

“I rejected the diagnosis,” admits Ames. “I thought bipolar was a sexy diagnosis, depression was kind of boring or average – It never occurred to me there was a type-two and I never had a manic period.”

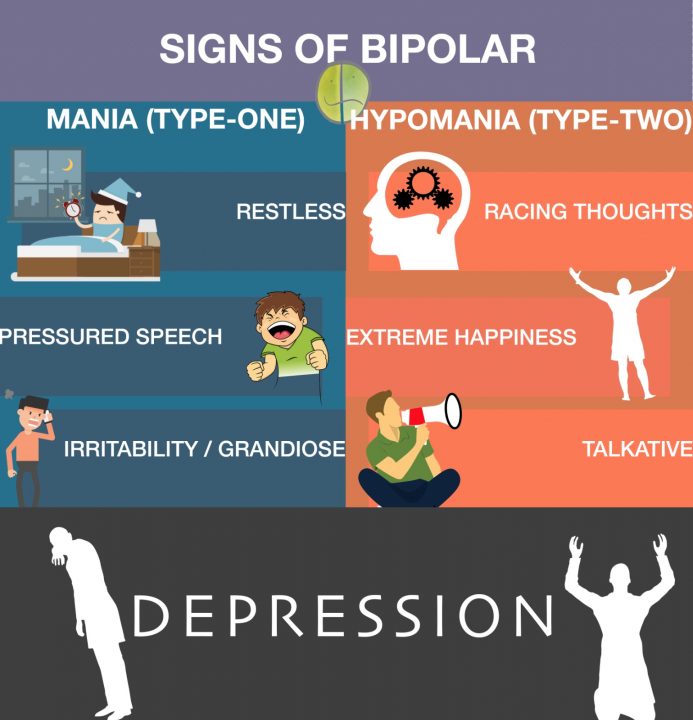

Stereotypes of mania overshadow subtler signs of type-two bipolar. Yet indicators like intensely great moods shifting to severe depression, a constant switching of ideas and responsibilities or an obscure sleeping pattern, help point towards it.

Eventually, Ames hit a crisis point. Her extravagant personality became tiresome. “My husband said get help or move out,” she repeats. When put in that position, Ames knew she needed an official diagnosis. Her hypomania which had always felt wonderful to her, was now burdened with huge restlessness and anxiety.

It’s been seven years since her diagnosis and medication proved to be the biggest struggle. When tackling depression, she refused anti-depressants. “I’m actually glad I hadn’t taken the anti-depressants then,” says Ames, as studies indicate they can trigger mania or a rapid cycling of moods. She also didn’t want Lithium – bipolar’s commonly prescribed drug – but in time she began treatment.

“I do have that fantasy all people with any diagnosis have, if I stop taking my meds, I’ll be fine,” Ames reveals. She pauses for a bit and acceptingly adds “I know that’s not necessarily true.”

ADJUSTING TO BIPOLAR:

To some degree, a person is changed when diagnosed with bipolar. Even though they were bipolar beforehand, diagnosis marks hope of a better future.

Christina Hajjar is still adapting to her new disorder after being diagnosed only four months ago. “I’m learning. I’m learning the way my mind works when I’m stable versus how my mind works when I’m hypomanic,” Christina says.

Like Ames, Christina believed she had depression. When correctly diagnosed, she was slowly introduced to her new medication. By six weeks, her depression began to fade away and she experienced what she believed was her first hypomanic episode.

“My brain was going off in a million different directions at the same time,” Christina explains “It’s not that negative of an experience, you get a lot accomplished – but it’s really sped up!”

Christina acknowledges she has little experience in being bipolar. Regardless, she feels reborn since the diagnosis. “I’ve had so many life experiences than I’ve ever had in the last five years,” exclaims Christina.

In her previous life, depression prevented her from properly socialising. Recently, she was swept away in an enchanting date and began reconnecting with old friends. “My best friend hasn’t seen me in years – the possibility of who I could be,” says Christina. “Now she’s getting to know me again and she’s in awe,” Christina adds gleefully.

Whilst Christina embarks on this new self-discovery adventure, she remains realistic. “They say with every up there’s a down with bipolar,” Christina mentions “If you’re high you’re going to crash.” Her depression is yet to return, but she “crashes” in the sense of utter exhaustion, after a day of energised hypomania climaxes in a feeling of depletion.

THE COST OF MEDICATION

In the US, being bipolar can be alarmingly expensive. In contrast, UK public health care provides free medication and therapy but rarely with long-term supervision of the same doctor.

Researchers into bipolar suggest that continuity of care – regularly seeing the same doctors and psychiatrists throughout treatment is the best way when tending bipolar.

Ames Elliot affirms “I’m in the best possible position to have a psychiatric disorder.” She acknowledges she’s privileged enough to afford substantial health care with her job’s great health insurance. Even then, roughly $10,000 a year of her medical and therapy costs isn’t covered by her insurance.

“It was clear to me I never would have made it if I didn’t have therapy visits every week,” believes Ames. She had two therapists, her counsellor which she called her head shrinker, and her practitioner which she called her drug dealer. The balance of treating herself both mentally and medically was key for regaining control.

Christina Hajjar believes Canadas health care system is progressive, with room for improvement. A large percentage of medicine costs is covered by insurance. However, it took six months to get a psychiatric appointment for an official diagnosis, so she sought random physicians. “What do you do in six months when you know you’re not okay?” asks Christina

It’s clear there’s still a long way to go in setting up an effective global system for bipolar. Long-term doctor and psychiatric visits are necessary to provide a strong support system and ensure bipolar is spotted earlier. Even 75% of patients who take Lithium experience nauseating side-effects.

There’s hope that by 2030, there will be a dramatically improved understanding in how bipolar can be better treated.

To find more about 'Bipolar: Breaking Stigma', follow the links below:

A Teachers’ Pain – MMP Radio Documentary

A Teachers’ Pain – MMP Radio Documentary