A former child miner has claimed that the working conditions in Congolese cobalt mines are so dangerous that workers live in the fear that they “could die at any moment.”

It is estimated by UNICEF that there are currently at least 40,000 children working in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s artisanal mines.

The children, some as young as 3-years-old, are forced to work 15-and-a-half hour days, digging for cobalt up to 180 metres underground.

Cobalt is a metal used in the manufacturing of the rechargeable Lithium-Ion batteries that are primarily found in laptops, smartphones, and electric vehicles.

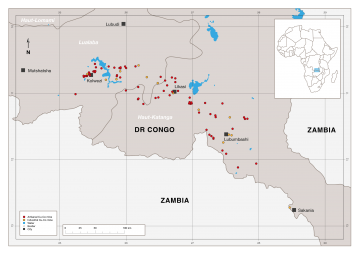

Citi estimates that in 2021 the cobalt industry will be worth around £4.3 billion, with roughly 60% of the planet’s supply being found in the DRC.

Whereas the children mining the metal receive the equivalent of around 32p for a day’s work in the mines, and it’s reported that 72% of the DRC’s 89.5 million population live in poverty.

Yannick*, a former child miner, suggested: “That’s if you were lucky enough to come out at all.

“The work is so dangerous you could die at any moment.”

Those words are spoken from personal experience, as both his brother and his friend died whilst working in the mine, and he claims to have seen children crushed and exploited by adults.

The Global Battery Alliance

While a solution to stopping children working in the mines on the surface may appear simple, Mathy Stanislaus, Interim Director of The Global Battery Alliance suggested it’s not as easy as “waving a magic wand” and saying, ‘get the children out of the mines.’

In fact, he claims: “Experience from people working on the ground tells us that simply doesn’t work.

“We have to not apply a Western mindset to this problem. We have to take a local community-lead perspective.

“How do you rebuild that (mining) community, with the community leaders leading?”

Mr Stanislaus suggested that there is no simple answer to his own question admitting that a solution would take many years and lots of investment.

He proposed that this is just as much a poverty issue as it is an abuse issue when he said: “Until you find alternative livelihoods, it’s still going to be a problem.

“You have to build a whole infrastructure. You have to create training programmes, education programmes, and the alternative forms of income,” he added.

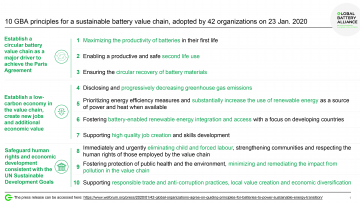

In January 2020, the GBA produced a set of ‘10 Principles for a Sustainable Battery Value Chain’, with number eight being:

‘Immediately and urgently eliminating child and forced labour, strengthening communities and respecting the human rights of those employed by the value chain.’

“It’s easy to say, it’s very hard to do,” admitted Mr Stanislaus. “The success is first based on building trust. Then working together on concrete demonstration of that trust.

“The manifestation of that requires time.”

Addressing shareholders and corporate leaders, Stanislaus stressed: “You have to respect the trust-building that is necessary for the kind of change that you say you want.”

The Big Businesses

Apple and Tesla are two companies who in the past who have been accused of violating human rights and exploiting child labour in the DRC.

Both have vowed to correct their practices and use responsibly sourced cobalt in their products. BUzz reached out to both for comment on how they intend to do so:

Apple: “We don’t have the resources to support every request, but I can point you to this article which includes a comment of ours:

“Apple is deeply committed to the responsible sourcing of materials that go into our products. We’ve led the industry by establishing the strictest standards for our suppliers and are constantly working to raise the bar for ourselves, and the industry.”

While Tesla replied stating they will not comment at this time, they pointed me to resources which read:

“Tesla recognises the higher risks of human rights issues within cobalt supply chains, particularly for child labour in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, we have made a significant effort to establish processes to remove these risks from our supply chain. We also recognise that mining conducted in a responsible and ethical manner is an important part of the economic and social well-being of those communities. We review all information provided by our suppliers for red flags and risks associated with ethical sourcing.”

UNICEF

One of the organisations on the ground working to find a sustainable and beneficial solution to the issue is leading children’s charity UNICEF.

They have acknowledged that there’s more to the issue than children being forced to mine:

“We only look at child labour, but we often lack the analysis of why it is happening. UNICEF have understood that first of all we need to ensure that the mining communities have access to basic social services.” Explained Mining Partnerships Coordinator, Daniella Savic.

“May it be a day nursery system, or primary and secondary education, or vaccinations and nutrition.”

“The issue is very systematic, which is why we need to go back to the root causes.” Ms Savic echoed Mr Stanislaus’s sentiment when she stated: “Simply taking a child out of a mine won’t resolve the issue.”

But, for former miners like Yannick, the memories of the mines are ever-lasting as he claims to “still see the sadness of the children.” Adding: “I can’t get the images of their suffering out of my head.”

Yannick continued, saying: “Every day was shocking, and it is important that the world hears our story.

“I demand the children have a voice.”

How can you help?

However, Mr Stanislaus has claimed that consumers in the West may be able to make a difference, simply by asking organisations the hard questions.

“Ask all manufactures how they the sourcing of their materials? How do you authenticate your greenhouse gas claims? That’s one way to help.”

Mr Stanislaus also noted that the general public can do their bit by supporting companies who bring scrutiny to the issue and buying from businesses that go out of their way to prove they operate in a responsible way, adding: “Purchasing power has some influence.”

*Name has been changed to respect the request of anonymity for fear of personal safety.

If you would like to learn more about the former child miners of the DRC, then you can check out The Cost of Cobalt to read further stories. You can also donate to Kit Out Kolwezi, an initiative that aims to raise money to support the education and social development of children recently out of the mines.

More from this project:

The Cost of Cobalt (Audio)

The Cost of Cobalt (Audio)