We all questioned the impact that the pandemic would have on our mental health. What not many anticipated was the toll it would take on children.

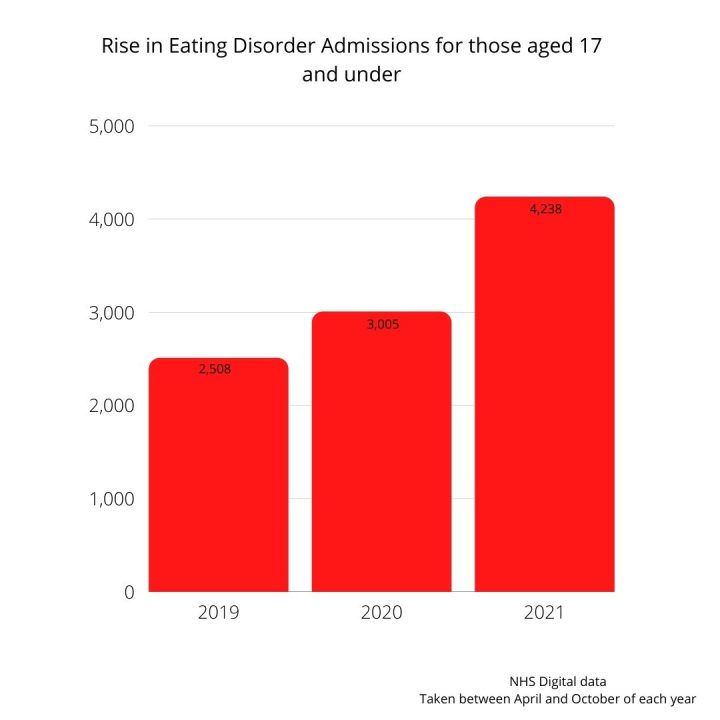

In the last year, hospital admissions for children with eating disorders, aged 17 and under, has risen by 41% since the 2020 statistics, and by 69% pre-pandemic.

Most likely due to the stresses of the pandemic and government induced restrictions, there has been a national surge; however, cases have been particularly higher in the South West and South East of the U.K. There has also been a surge in comorbidity cases in Dorset.

Nicole Grilo, founder and therapy manager at Ashley Cross Eating Disorder Service in Poole, says that the onset of eating disorders resurfaced in young people around March 2020 and February 2021. All correlating with lockdown.

“Mental health issues are exacerbated by a lack of access,” says Nicole. “This could be a lack of access to friends, social situations, support and services.”

Nicole added that a rise in social media use would have been a major influence that would have triggered eating disorder behaviours.

While eating disorders are mental illnesses, the physical implications that are caused can be just as, if not more, damaging.

This has meant that since the pandemic, there has been a 20% rise in physical and medical interventions such as an ECG to check heart health or weekly weigh ins.

“Just the staff needed to facilitate even low risk physical monitoring, has increased further to high-risk monitoring such as overnight stays, 24-hour monitoring and health care assistance.”

Lyn Hill lives in Bournemouth and is a mother to 16-year-old Becky who was diagnosed with Anorexia Nervosa at the age of 10.

While Becky has made a lot of progress since her diagnosis, when the pandemic hit, things started to fall again and Lyn has not been able to get access to crucial medication for Becky, describing it as “exhausting”.

“The lockdowns have really exacerbated her anxiety,” says Lyn. “She couldn’t cope seeing people in face masks as it brought back old memories from when she was receiving treatment in hospital.

“It’s so frustrating. I know my daughter and I know what she needs, and I can’t get it. But I do understand it is no ones fault- we’re in a pandemic.”

When she first took Becky to her local GP she was turned away and was told that Becky wasn’t underweight enough to receive help.

One month went by and Lyn went back to the GP with Becky weighing in one stone lighter.

Becky was admitted to hospital 7 months later. Lyn described it as the hardest thing she has ever had to do.

“By that time, it had broken me,” says Lyn.

“It gave us some rest bite however, as I knew she was safe, and I could put myself back together.”

Despite cases of eating disorders sky rocketing, it is not a recent phenomenon that there aren’t enough spaces in hospitals for eating disorder patients.

While extra wards have been built to increase bed capacity in Dorset, such as the two-storey ward built at St Ann’s in Poole in 2020, finding a local bed can still be a challenge.

When Becky was admitted, she was sent to a hospital 2 and a half hours away from home and was a general hospital. It was not an eating disorder specialist ward which Lyn struggled with.

“Because it was a general hospital, mealtime was very difficult for Becky because they couldn’t tailor to her needs,” says Lyn.

She added that the distance also was difficult as she couldn’t call her daughter every night.

However, recent changes to beds available to young people has meant that if you are diagnosed in the South West, you will remain in the south West to receive hospital treatment.

Previous regulations meant that if you needed a bed under the age of 18, you could be sent to any space available in the country.

Nicole says that this has change has decreased the time patients spend in a general hospital while waiting for an eating disorder bed and will be easier on families.

Despite the struggles, Becky and her mother did receive endless support from YPEDS (Young Persons Eating Disorder Service), who were able to provide them with meal help, therapy and family therapy.

Nicole outlines the importance of recognising the early signs of eating disorders, before medical intervention is needed, even though they can often be hard to spot.

“Early signs can be so varied. For example, if a child is wanting to eat different things at the table than their family, want to eat on their own or if a parent hasn’t seen their child physically eat in a while can all be warning signs.”

We reached out to Public Health Dorset and Dorset HealthCare for a statement however they were unable to get back to us.

If you think you may be suffering with an eating disorder or are worried about someone else’s health, there are multiple groups you can go to for support.

BEAT Eating disorders:

Helpline: 0808 801 0677

Email: help@beateatingdisorders.org.uk

Dorset HealthCare University (Carers support group):

03000191771

dhc.eatingdisorders@nhs.net

Dorset Police referred to police watchdog after teen deaths

Dorset Police referred to police watchdog after teen deaths