Conversations around mental health and gaming tend to follow the same train of thought. Violence, addiction, and our ever-growing dependence on technology. Earlier this year the World Health Organisation released their classification of gaming disorder, and while it’s important that we look at the risks gaming poses, it can be equally as important to take a step back and look at how it can help us.

In recent years, a number of ‘serious’ games have begun to surface. So-called because they deal with serious themes and are designed to inform and aid its players. One of these games is Champions of the Shengha, developed by BFB Labs and the Shift charity. It aims to teach young people about emotional regulation, by playing the game with a heart-rate monitor.

Duncan Brown, development director at the Shift charity, says that the game is a preventative product. It teaches children the skills to deal with difficult emotions before the onset of mental health problems like anxiety and could act as a useful addition to usual therapy.

“Some therapy has been adapted to young audiences but they’re just not engaging user experiences for them, so we set out at the completely other end of the spectrum and said if we’re going to have any hope of teaching these skills to young people, we must build an experience that they genuinely want to use.

The critical thing with children is that they use it not because they want to learn to emotionally self-regulate – what they are motivated to do is play a cool video game.”

Michelle Colder Carras, of Radboud University in the Netherlands, researches the effects of video games on mental health in the Games for Emotional and Mental Health (GEMH) lab. The lab’s work has yielded similar results to that of Shift.

“We have similar games to Champions of the Shengha in the GEMH Lab. We’ve done trials in a real-world setting where we’ve shown that one of our games, Mind Light, has led to the same amount of reduction in anxiety as CBT that’s done in schools,” she says.

But as much as there are issues with commercial games, games for health have drawbacks as well. Carras believes that game developers should be working closer with clinicians and researchers to make a truly effect game for health.

“Game developers may make great games, but they may not have the best understanding of what kind of scientific evidence is needed to support using the game for a specific mental health goal, and clinicians and researchers may have a good understanding of how to design studies to test games but may not be able to produce a really gorgeous game.

Big game companies have the ability to provide data and they even have the ability to do experiments within the games, so if we can develop the proper collaborations then we have the ability to test hypotheses about social interaction or achievement or other things we know are important for commercial games and mental health, in way that just hasn’t been done yet.”

In her study of the effects of video games on the mental health of military veterans, Carras’ participants reported some surprising positive effects of gaming on their mental states, despite some of them showing signs of gaming addiction.

“There were a few veterans that said, ‘Games are a way of me not thinking about committing suicide’ or ‘I put gaming into my day because I crave alcohol all day and I don’t want to relapse’.

There’s that prospect of using games for harm reduction, and of using games to distract from suicidal thoughts. Sometimes people aren’t able to think of the things they’ve been taught in therapy, they just don’t come to you when you’re in the moment and you need something else to take your mind off of these thoughts,” she explains.

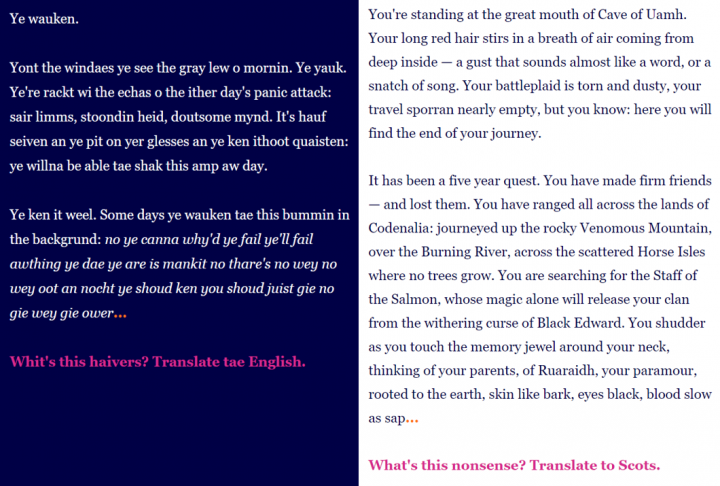

Though using escapism as a way to cope isn’t limited to playing the games. This was true for Harry Josephine Giles, sole creator of the game Raik.

“I was having a hard time,” he says, “living by myself for the first time in my life, in a cold and damp flat, after a break up, and so vulnerable at the worst of my mental health. I just needed to express that experience.

For me, working on a large project with a lot of technical details is a good way of dealing with the difficult emotions. On the one hand, it’s a distraction; on the other hand, the slow pace allows you to spend a lot of time with the emotions in a safe way. Coding a mechanic to replicate a panic attack is a much safer way of dealing with trauma than performing a poem about a panic attack.”

For Giles, it was a very personal project: “I never really had ambitions beyond expressing a particular thing in a way that interested me! But a few folk wrote to say they identified with it, were helped by it. But it’s not an advocacy game, or a game for change. Trying to express oneself honestly is going to generally lead to better art and better advocacy than starting with the aim of being an advocate.”

As technology evolves, so does our understanding of how it fits into our daily lives. Video games are becoming a much more accepted art form, and now it looks as though there’s a gap in the market for them to become a significant aspect of therapy. Looking to the future, game designers and researchers alike seem to have a unique opportunity to make a difference to those who suffer from mental health – some are making that difference already and may not even realise it.

As Duncan Brown puts it: “These types of game can’t replace face to face therapy, but when you look at the spectrum of needs around something like anxiety, therapy could happen more effectively if supported by better products that reinforce some of the protocols outside of therapy sessions.

I’m absolutely sure that in 10 years’ time we will have an armoury of really well-designed digital products which are exactly suited to engage audiences and really deliver on the therapeutic aspects that can be embedded in them. The way that games can help won’t be overlooked much longer.”

Learn more about how games are helping mental health

A Contested Life

A Contested Life